Friends of Woodthorpe Grange Park 2023

Sherwood Looks To Tomorrow:

And So Must We All

Nottingham Observer, July 1969

“A Warning from the Past, May 2025”

Major Oak, Sherwood Forest

‘Wha’s’ the goddam trees?’ demanded the indignant American tourist who last week blocked the entrance to Sherwood Bus depot with around 20 feet of chrome-draped automobile while he asked.

He was looking for Sherwood Forest and there was no shortage of amused passers-by to answer his question. For the England that once sprouted oaks with such fertility has long switched to people production on a more ambitious scale. And, unlike the outlaws, who loved to glug the wine nicked from the Abbot among the leaves so green-O, later people preferred their pre-prandial noggin in the shade of their little semi. So, regretfully, they chopped lots of the forest down.

Our disgusted U.S. visitor had a tidy drive from ‘The old streetcar Deepo’ to the ‘Quaint bit of Old Country’ we wanted to see. Not the limb of Nottingham now called Sherwood had for scores of centuries been much more than the straggling southern tip of the great wood that was. But little more than 300 years ago, Sherwood Forest was still 20 miles long, rolling northward, and some eight miles wide, covering 100,000 acres. That’s roughly one-fifth of the whole of Nottinghamshire.

Sherwood Oak was long prized for the building of great houses and the stout ships that bossed the seas; Welbeck oak, a favoured section went into the rebuilding of St. Paul’s Cathedral; and throughout the forest, our ancestors replaced the timber they had taken, with far-sighted schemes or replanting. The oak trees proliferated till comparatively recent times, for the very large eighteenth-century replanting’s, and might yet have withstood the ravages of time and the axe but for atmospheric pollution. Now they are largely gone and the survivors as they dwindle are being replaced by conifer and beech.

Happily, for what is left of the forest that once nudged the skirts of the city, the Forestry Commission entrenched itself amid its greenery in 1925 and has worked tirelessly since to preserve some of the history and the beauty of Sherwood Forest for posterity. From their Edwinstowe base, the Forestry men gradually extended the area under their lien to embrace 16,000 acres, or 25 square miles; caring for the timber by judicious thinning, protecting it from disease and replanting the area with systematic dedication. The Commission was founded 50 years ago (June 1919) last month, and the job it is doing to mend parts of a Bruised Britain and to fend off further encroachments will probably not win true appreciation for a century or two yet.

Meanwhile, we have quite deliberately led you along the diversionary paths of Sherwood Forest today before coming back to the city suburb that bears its name. Because Sherwood the suburb is a microcosm of what has happened, is happening, and is likely to happen to this country in the future. The whole of Britain is under siege; its forest, its fields, its manors, its churches, and its old pubs.

Hamlet is swallowed by village, village by town, town by city. We’ve got used to this; people have to live somewhere. We’ve got used to the supermarket standing where the redundant church used to be, and the indecipherable gravestones did make splendid hardcore for the customers’ carp park. (How come this surfeit of expendable churches in an area with a steeply rising population?)

But now a new phenomenon looms, open-mawed, to gulp the whole blessed lot of us. A hideous monster we name. The Conurbation.

A conurbation is a thing that would be a vegetarian at heart if it had a heart but it hasn’t that is what makes it a conurbation. No punctuation, that’s a conurbation. It eats grass. And everything that has the slightest smell of grass. It is quite simply, by filling in the green spaces between cities, towns and villages, with more tarmac and tiles. So that each established place loses its identity and its heart and its engaging little ways, and merges in one great, sprawling, featureless mass; teeming with ants who hate every other ant, with a kind of hopeless impotent ferocity. Exquisite refinements of hell are presented in the conurbations of Los Angeles and New York.

Character murder like broadcasting that your neighbour is a frequenter of brothels pales beside the character-throttling perpetrated by upright representatives of the people in the name of progress. Concrete lasts.

So too, up to now, has Sherwood’s claim to a degree of individuality lasted; born of a past separate from the city that absorbed it in 1877 and the fact that it breathes the fresh air of the open Nottinghamshire Countryside just beyond its boundaries. But now Sherwood could be one of the places due to being hemmed in by endless miles of urban sprawl and rendered utterly featureless by redevelopment as an integral part of an expanded super city centre. Bureaucracy might then be minded to award the district a more informative location name. How about North Precinct Five?

Up until the First World War Sherwood had done pretty well in keeping its separate identity. It was typical of scores of other English towns whose autonomy had gone because of their proximity to fast-growing big neighbours whose urban development had at one point or more rolled to close the gap between them. Sherwood had remained a largely residential district, with many imposing houses, some of which still survive. It used to have its own railway station, from which people travelled to work in the comfortably at-arm’s-length city centre: and to sister towns on the periphery, passing through stretches of now-vanished open country on the way.

The city had not made its authority felt in a manner likely to lead to the merry men of Sherwood kidnapping the Sheriff. Though not all residents admired the beautifully constructed building the council graciously endowed them in 1892: Nottingham Prison, then called Bagthorpe Gaol, was not felt to be the ideal civic amenity with which to celebrate the 15th year of marriage between city and town, particularly when gentlemen were brought to the place for official engagements that terminated abruptly when the platform gave way: last hanging at the prison was many years ago.

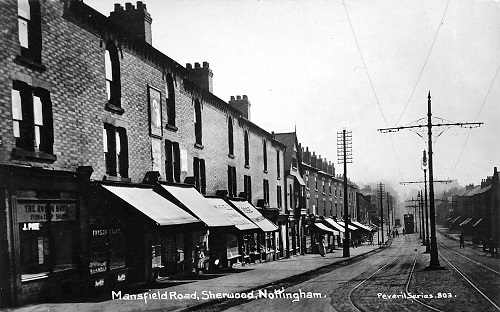

Circa 1900: Mansfield Road, Sherwood

A diversity of trade gradually found a home in Sherwood. Lace-making of course was one of the earliest. The manufacturing of paper and bicycles came together with cabinet making, bleaching and dyeing, dressmaking, laundering and the manufacturing of small furnaces.

Some of our readers will argue that the provision of amenities surely outweighs the disadvantages that follow the urbanisation of a village or the disappearance that follow the urbanisation of a village or the disappearance of a distinctly separate town in the tentacle embrace of a nearby commercial octopus. And up to a point they have a case, though few of the amenities of the modern city are not also available to the village. A notable concession in Sherwood is the excellent shopping centre: many people travel some distance into the district to shop because of its reputation for range and value for money.

But what price these shops if at some date in the future the new super-council proposed by the Boundaries Commission (who propose powers at present only vaguely defined), should decide that Sherwood must be a Commercial Development Area and that the shops bull-dozed to make way for giant office blocks? Far-fetched? Look at the way people were ejected from the City of London by Mammon.

And anyway, when we shrug off something as a disadvantage what do we mean? Usually that we are not personally involved. If a man has a knife at his throat, it could be said that he is at a disadvantage. But if the other fellow doesn’t stay his hand the observation ceases to cover the case.

Progress never stays its hand. Be it advantageous or disastrous. Whatever the effort involved, therefore, it is our responsibility to watch the things being done in its name and to try to exercise some influence over the course. A charming village may become a pleasant town, the town a fair city. Like Nottingham. Are we sure though that we are going to like the new city at is being evolved with such haste at the moment? Is everyone happy about the development of Greater Nottingham?

No. The East Midlands Economic Planning Council has this to say: ‘Greater Nottingham is in fact rapidly becoming a vast urban tract which, with Derby and the lower Erewash Valley, is in danger of becoming a continuous area of urban development exhibiting the characteristics of a traditional conurbation.’

2021: Mansfield Road, Sherwood

If we believe that this will not affect the established pleasant local town or suburb we live in, or that we can follow the past pattern of moving a little further out, we ate in error. If we stay put, we are going to see our neighbourhoods deteriorate fast. If we prospect the possibilities of moving back, we are going to find bricks, concrete and people coming the other way.

The Planning Council warns on the urgent need for good planning to accommodate an increasing population without creating congestion and a poor environment Sherwood would be just one of those places squeezed between the inexorable growth of the city and mushroom growth on the outer periphery as the green space between towns moved towards vanishing point.

Sherwood is picked on as an excellent example of a place critically involved in the changing scene. However much we may wish that it could have remained the village of long ago we know the thought is idle. But the American hunting for Sherwood Forest didn’t come to England just to see this: readers who have visited the States will know that it has some matchless natural beauties of its own. Tourists are attracted to this country by its remaining examples of a long history. Only the British don’t seem to care very much about their heritage the majority watching it being eaten up without a murmur. In Sherwood, our microcosm of England, the people have managed to build on to some of the past; not very old, but still of a much more gracious age than we share. That they should now be allowed to keep hanging on to it is not just their problem but ours too; we are all going to be in the same boat in a minute.

At County House, High Pavement, Nottingham County Council Record Committee are holding a commemorative display of Nottinghamshire records to celebrate the centenary of the Historical Manuscripts Commission, from now till 30th September “1969.” The documents on show date back to the 12th century and mirror England so much slower and greener – and occasionally darker – than our own.

The documents include a fascinating warrant from Thomas Lord Viscount Wentworth to Sir Francis Foljambe, dated in 1629 and adjuring him to look to the poaching peasantry, beginning thus:

‘Perceiveinge the great abuses and enormyties practized by sundry of idle persons and men of loose life and meane quallite in the unlawful destruction of all sortes and kinde of Game, as deare, Haires, Connyes, Pheasant, partridges, Quailes and Moore Game and Greyhoundes, Houndes, Settinge doggs, Gunnes…Hairepipes, cords and other ingines…’

Those were the dayes my friendes. No shortage of local enterprise – or fields and forests to deploy it in. A member of that ingenious fraternity coming back to life now might find his talents rather circumscribed. He might in fact echo a recent question: ‘Wha’s the goddam trees?’

Return